In the icy waters north of Russia, discarded submarine nuclear reactors lie deteriorating on the ocean floor—some still fully fueled. It’s only a matter of time before sustained corrosion allows seawater to eat its way to the abandoned uranium, causing an uncontrolled release of radioactivity into the Arctic.

For decades, the Soviet Union used the desolate Kara Sea as their dumping grounds for nuclear waste. Thousands of tons of nuclear material, equal to nearly six and a half times the radiation released at Hiroshima, went into the ocean. The underwater nuclear junkyard includes at least 14 unwanted reactors and an entire crippled submarine that the Soviets deemed proper decommissioning too dangerous and expensive. Today, this corner-cutting haunts the Russians. A rotting submarine reactor fed by an endless supply of ocean water might re-achieve criticality, belching out a boiling cloud of radioactivity that could infect local seafood populations, spoil bountiful fishing grounds, and contaminate a local oil-exploration frontier.

“Breach of protective barriers and the detection and spread of radionuclides in seawater could lead to fishing restrictions,” says Andrey Zolotkov, director of Bellona-Murmansk, an international non-profit environmental organization based in Norway. “In addition, this could seriously damage plans for the development of the Northern Sea Route—ship owners will refuse to sail along it.”

News outlets have found more dire terms to interpret the issue. The BBC raised concerns of a “nuclear chain reaction” in 2013, while The Guardian described the situation as “an environmental disaster waiting to happen.” Nearly everyone agrees that the Kara is on the verge of an uncontrolled nuclear event, but retrieving a string of long-lost nuclear time bombs is proving to be a daunting challenge.

Nuclear submarines have a short lifespan considering their sheer expense and complexity. After roughly 20-30 years, degradation coupled with leaps in technology render old nuclear subs obsolete. First, decades of accumulated corrosion and stress limit the safe-dive depth of veteran boats. Sound-isolation mounts degrade, bearings wear down, and rotating components of machinery fall out of balance, leading to a louder noise signature that can be more easily tracked by the enemy.

At the same time, newer vessels incorporate the latest advances in power plant technology, metallurgy, hull shape, low-friction coatings, and propeller design, making for faster, quieter, deeper-diving, and more deadly undersea combat vessels. “Technology advances and proliferation will make the submarine's stealth, endurance, and mobility even more important attributes in the future,” says a 1998 Defense Science Board Task Force report. In combat, older subs won’t cut it.

The Soviet Union and Russia built the world’s largest nuclear-powered navy in the second half of the 20th century, crafting more atom-powered subs than all other nations combined. At its military height in the mid-1990s, Russia boasted 245 nuclear-powered subs, 180 of which were equipped with dual reactors and 91 of which sailed with a dozen or more long-range ballistic missiles tipped with nuclear warheads.

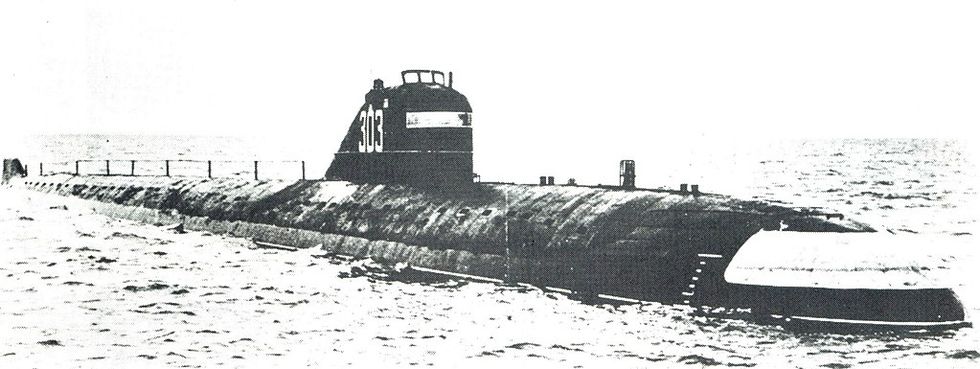

The Soviet Union’s first nuclear-powered submarine was the K-3, the first of the NATO code-named November class (the Soviets called them the “Whale class”). The K-3 prototype sailed for the first time using nuclear power on July 4, 1958. All but one of the 14 November class vessels cruised with dual VM-A water-cooled nuclear reactors, with the final sub, the experimental K-27, powered by a pair of VT-1 liquid metal-cooled reactors.

The November class vessels were top-of-the-line attack submarines designed to locate surface vessels and opposing submarines using a powerful MG-200 sonar system. Once in range, Novembers would strike with ship-killing 533mm SET-65 or 53-65K torpedoes, each carrying up to 300 kilograms of hull-shattering explosives.

Eight hotel-class submarines, built to house and launch a complement of ballistic missiles, joined the Soviet fleet between 1959 and 1962. While Novembers were the USSR’s hunters, the Hotel-class subs were meant to stay undetected, using a pair of pressurized water-cooled reactors to cruise within striking distance of potential targets. Once enemy military bases or civilian population centers were in range, a Hotel class sub could unleash a barrage of R-13 or R-21 nuclear missiles, each of the latter with a blast yield of 800 kilotons. A strike of this magnitude over Midtown Manhattan would probably kill over two million people, according to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Fatalities would extend to parts of Queens, Brooklyn, and sections of New Jersey west of the Hudson.

Echo-class Soviet nuclear submarines took to the seas in 1960. These housed twin water-cooled reactors and carried conventional and nuclear-tipped cruise missiles, along with a complement of torpedoes. The Soviets built five Echo Is—equipped with six P-5 turbo-jet powered cruise missiles to hit targets on land—then launched 29 Echo IIs, specifically equipped with anti-shipping missiles meant to neutralize American aircraft carriers.

A majority of the Soviet’s nuclear submarine classes operated from the Arctic-based Northern Fleet, headquartered in the northwestern port city of Murmansk. The Northern Fleet bases are roughly 900 kilometers west of the Kara Sea dumping grounds. A second, slightly smaller hub of Soviet submarine power was the Pacific Fleet, based in and around Vladivostok on Russia’s east coast above North Korea. Additional Soviet-era submarines sailed from bases in the Baltic and Black Seas.

For decades, these pioneering Soviet submarine classes served around the world, awaiting the moment when the Cold War would turn hot. That moment never came. By the mid-1980s, the boats were reaching the end of their useful lifespan. Starting in 1987, the oldest Echo Is left the fleet for decommissioning, and November class attack submarines followed in 1988. But the disposal of these submarines posed more problems than previous conventional vessels. Before crews could chop the vessels apart, the subs’ reactors and associated radioactive materials had to be removed, and the Soviets didn’t always do this properly.

Mothballed nuclear submarines pose the potential for disaster even before scrapping begins. In October of 1995, 12 decommissioned Soviet subs awaited disposal in Murmansk, each with fuel cells, reactors, and nuclear waste still aboard. When the cash-strapped Russian military didn’t pay the base’s electric bills for months, the local power company shut off power to the base, leaving the line of submarines at risk of meltdown. Military staffers had to persuade plant workers to restore power by threatening them at gunpoint.

The scrapping process starts with extracting the vessel’s spent nuclear fuel from the reactor core. The danger is immediate: In 1985, an explosion during the defueling of a Victor class submarine killed 10 workers and spewed radioactive material into the air and sea. Specially trained teams must separate the reactor fuel rods from the sub’s reactor core, then seal the rods in steel casks for transport and storage (at least, they seal the rods when adequate transport and storage is available—the Soviets had just five rail cars capable of safely transporting radioactive cargo, and their storage locations varied widely in size and suitability). Workers at the shipyard then remove salvageable equipment from the submarine and disassemble the vessel’s conventional and nuclear weapons systems. Crews must extract and isolate the nuclear warheads from the weapons before digging deeper into the launch compartment to scrap the missiles’ fuel systems and engines.

When it is time to dispose of the vessel’s reactors, crews cut vertical slices into the hull of the submarine and chop out the single or double reactor compartment along with an additional compartment fore and aft in a single huge cylinder-shaped chunk. Once sealed, the cylinder can float on its own for several months, even years, before it is lifted onto a barge and sent to a long-term storage facility.

But during the Cold War, nuclear storage in Soviet Russia usually meant a deep-sea dump job. At least 14 reactors from bygone vessels of the Northern Fleet were discarded into the Kara Sea. Sometimes, the Soviets skipped the de-fueling step beforehand, ditching the reactors with their highly radioactive fuel rods still intact.

According to the Bellona, the Northern Fleet also jettisoned 17,000 containers of hazardous nuclear material and deliberately sunk 19 vessels packed with radioactive waste, along with 735 contaminated pieces of heavy machinery. More low-level liquid waste was poured directly into the icy waters.

One of the most egregious and dangerous disposal capers was that of the K-27, the experimental November-class submarine with two liquid metal-cooled reactors. While at sea in 1968, one reactor aboard the K-27 suffered a leak and partial meltdown. Radiation exposure killed nine crewmen and sickened 83 more. The K-27 limped back to port, but after years of analysis, naval crews deemed it impossible to save. In 1981, tugs towed K-27 into the Kara and scuttled the hulk, sending everything—fuel, reactors, and other waste—to the bottom. Experts suggest safely sinking nuclear material to at least 3,000 meters. The K-27 lies at 50 meters.

In 2012, a joint Norwegian/Russian inspection of the K-27 wreck revealed little deterioration—but naval experts think the sub might only stay intact until 2032.

Another submarine is perhaps a bigger risk for a radioactive leak. K-159, a November class, suffered a radioactive discharge accident in 1965 but served until 1989. After languishing in storage for 14 years, a 2003 storm ripped K-159 from its pontoons during a transport operation, and the battered hulk plunged to the floor of the Barents Sea, killing nine crewmen. The wreck lies at a depth of around 250 meters, most likely with its fueled and unsealed reactors open to the elements.

Russia has announced plans to raise the K-27, the K-159, and four other dangerous reactor compartments discarded in the Arctic. As of March 2020, Russian authorities estimate the cost of the recovery effort will be approximately $330 million.

The first target is K-159. But lifting the sunken sub back to the surface will take a specially built recovery vessel, one that does not yet exist. Design and construction of that ship is slated to begin in 2021, to be finished by the end of 2026. Now, in order to avoid an underwater Chernobyl, the Russians are beginning a terrifying race against the relentless progression of decay.

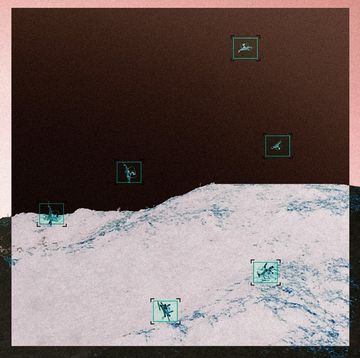

Video by Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority